THE STORY OF RESCUED FISH

How $650,000 worth of Patagonian Toothfish nourished those who could least afford it

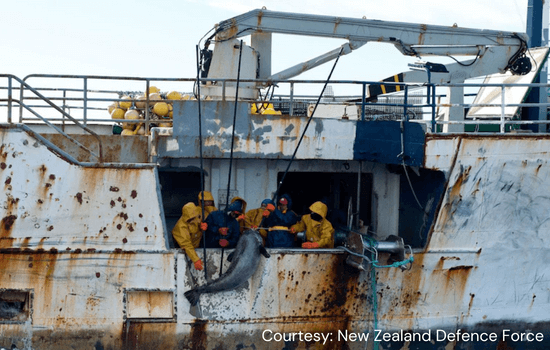

You won’t have seen Patagonian Toothfish through the glass at your supermarket deli, but likely you’re familiar with the name through news stories of pirate fishing boats being chased through sub-Antarctic waters.

These elusive predatory sea monsters, are a deep-water species, found 50 to 3000 metres from the surface. They live 50 years, growing slowly to a length of 2 metres. Patagonian Toothfish may be top of the food chain among fish, but they are in decline, having fallen prey to illegal fishing practices which feed Asian black markets.

Responsibly sourced Patagonian Toothfish fetches a premium price in excusive restaurants, so few can say they’ve tried it. Yet back in 2005, $650,000 worth of the fish made its way to the tables of those most in need. This story is almost legend at Foodbank WA, much like the man we asked to tell the tale, our recently retired General Manager of Operations, Steve Martin.

Steve was at the time working as State manager for Swire Cold Storage, the largest cold storage company in WA. The company received a shipment from a seafood import company which supplied the restaurant trade around the Perth area.

“There was a 20-foot container of fish imported and in it was six and a half tonne – 6500 kilos – of Patagonian toothfish, which I think was valued at about $100 a kilo. At that time there was a lot of focus on importation of the product because of poaching by Chinese and Russian fishing trawlers around Herd Island, which is where they catch this prehistoric fish,” said Steve.

“When it entered the country documents were presented for quarantine, but there was an issue. I’m guessing it was the certificate of origin which determines where the product is sourced and whether it’s legally fished. Our company had unpacked and stored the product, so quarantine served a notice on us. It had to be quarantined – it couldn’t be sold or released until authorisation was given by Quarantine.”

The importer went to court to fight for release of the product which they understood to be legally fished, but the documentation didn’t stand up in court. Six months later, Steve’s company was served a notice that the frozen fish had to be dumped – under supervision.

“Representatives from my company, from the importer and from Quarantine had to accompany the fish to a rubbish tip and witness it being bulldozed into the ground,” said Steve. “And I thought ‘well that’s a nonsense. It’s healthy, wholesome, nutritious. There’s nothing wrong with the product.’”

Although it would be several years before Steve took up a role with Foodbank WA, he was at that time already a passionate advocate for our cause. Steve was involved since day one, following an approach by Foodbank’s founding CEO GM Doug Paling.

“Doug described the Foodbank concept with great passion. Working in the food industry, I saw a lot of waste and I thought ‘wow, how great to be able to distribute food that the industry dumps for a variety of reasons – silly labelling issues, packaging damage or slow-moving product,” said Steve.

I saw an opportunity to be an advocate for Foodbank WA and channel food to them, firstly through my role at I&J foods then over the years through other companies including Swire Cold Storage.

As Foodbank WA grew, so did Steve’s involvement. His expertise was welcomed and when the valuable container of toothfish landed in Swire’s freezers, he had a seat on Foodbank WA’s Operations Committee.

Dumping 6500 kilos of good fish was “nonsense” Steve couldn’t ignore. He picked up the phone and set up a meeting with Quarantine.

“They agreed it was wrong to be burying the product when people in the community could benefit from it. They gave me authorisation to release it to Foodbank WA, we delivered it and it went out through the Foodbank network.”

Steve says that although the portions of fish would have been plastic wrapped and labelled, it’s likely most of those received the fish would not have known what they were eating. Food was distributed mainly through a network of agencies, often packed as part of a hamper with a variety of foods.

The Patagonian Toothfish story has one final chapter, one that remained untold for nearly 15 years. Steve was invited to speak at a luncheon in Albany and he recounted toothfish story to illustrate Foodbank’s reliance on food diverted from landfill.

“Afterwards, a lady came up to me and wanted to give me a hug. She said her family were actually recipients of some of that fish,” said Steve.

“She told me her story about how her family had fallen on hard times. They were really struggling and she was extremely grateful and thankful for the support the Foodbank WA was able to provide. She said it played an important part in getting their lives back on track, and that she was living a happy full life again.”

“It was a really good news story and it was nice to actually meet an end recipient who benefited from rescued food – fish that could have just been bulldozed into the earth”

We don’t often get to see the final stage of our work at Foodbank WA, but when we do, there’s no greater job satisfaction. That has to be worth a whole lot more than $100 a kilo. Right?

Contact us

Contact us Log in

Log in